Owls remain among the most captivating yet elusive birds on our planet. With their silent flight, exceptional hunting abilities, and mysterious nocturnal habits, these birds of prey have fascinated humans across cultures and throughout history.

Whether you’re an experienced birder seeking to refine your identification skills, a wildlife photographer hoping to capture these enigmatic hunters, or a nature enthusiast curious about the owls in your region, accurate identification is both challenging and rewarding.

In this comprehensive guide, we’ll explore all owl-related facts by combining detailed physical identification markers with behavioural cues, habitat preferences, and regional variations, elements often overlooked in traditional field guides.

By understanding not just what owls look like but how they behave and where they live, you’ll develop a more holistic approach to owl identification that works both day and night, across continents, and in various environmental conditions.

Key Takeaways

- Owls belong to two distinct families: Tytonidae (barn owls) and Strigidae (true owls), with 234 recognised species worldwide

- Physical identification relies on size, facial disc structure, eye colour, ear tufts, and plumage patterns

- Behavioural cues, including hunting techniques, flight patterns, and vocalisations, are crucial for accurate identification

- Regional adaptations vary significantly, requiring location-specific identification approaches

- Conservation status affects the likelihood of encounters, with many species becoming increasingly rare

- Ethical observation practices are essential to protect sensitive species, particularly during breeding seasons.

Understanding Owl Classification and Evolution

Owls have a fossil record dating back approximately 60 million years, with modern owl families established about 40 million years ago. Today’s owls are classified into two distinct families: Tytonidae (barn owls) with 20 species featuring heart-shaped facial discs and slender bodies, and Strigidae (true owls) comprising 234 species with more rounded facial discs and generally stockier builds.

Recent genetic studies have revolutionised our understanding of owl relationships, sometimes contradicting traditional classification based on physical characteristics. For example, the Oriental Bay Owl (Phodilus badius) was reclassified from Strigidae to Tytonidae based on DNA analysis, despite its physical resemblance to typical true owls.

How many species of owls exist worldwide?

There are 254 recognised owl species globally across 25 genera, though this number occasionally changes as new species are discovered or existing ones are reclassified through genetic research.

Essential Owl Anatomy for Identification

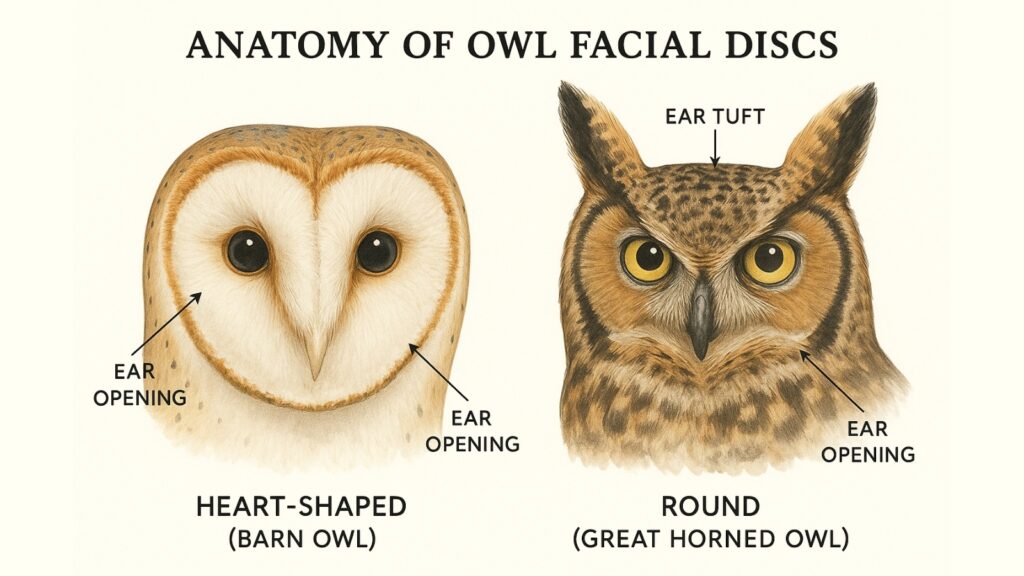

The Facial Disc: Nature’s Sound Parabola

The facial disc serves as perhaps the most distinctive feature for owl identification at the family level. This concave arrangement of specialised feathers directs sound to the ears, enhancing the owl’s already exceptional hearing.

- Tytonidae (barn owls): Heart-shaped facial disc, often with a distinctive ridge or frame

- Strigidae (true owls): Rounded facial disc with varying degrees of definition.

The facial disc’s shape, colouration, and definition provide immediate clues to identification. For example, the Western Barn Owl (Tyto alba) has a stark white, heart-shaped face that appears almost ghostly in flight, while the Great Horned Owl (Bubo virginianus) has a more subdued, brownish facial disc interrupted by its prominent ear tufts.

Eyes: Windows to Species Identity

Unlike most birds, owls have forward-facing eyes that provide binocular vision similar to humans, aiding in hunting and depth perception. Eye colour varies significantly between species and can be a key identification marker:

- Yellow eyes: Most common, found in species like the Great Horned Owl and Barred Owl

- Dark brown/black eyes: Less common, characteristic of Barn Owls and Northern Saw-whet Owls

- Orange eyes: Found in species like the Flammulated Owl

- Striking red-orange: Distinctive feature of African Wood Owls.

Eye colour sometimes changes with age, making it important to consider other identification features when observing juvenile birds.

Ear Tufts: Not Ears at All

Despite their name, ear tufts have nothing to do with hearing. These feather tufts are purely visual features that vary dramatically between species:

- Prominent ear tufts: Great Horned Owl, Long-eared Owl, Eurasian Eagle-Owl

- Moderate ear tufts: Eastern Screech-Owl, Tropical Screech-Owl

- Minimal or absent ear tufts: Barn Owl, Barred Owl, Snowy Owl.

Ear tufts can be raised or flattened depending on the bird’s mood, affecting its appearance significantly. This behavioural aspect must be considered when using ear tufts for identification.

Size and Proportions: Scale Matters

Size provides an immediate identification clue, especially when comparing owls in the same habitat:

- Giant owls (450-700mm tall): Blakiston’s Fish Owl, Eurasian Eagle-Owl, Great Gray Owl

- Large owls (400-500mm): Great Horned Owl, Snowy Owl, Barred Owl

- Medium owls (250-400mm): Barn Owl, Short-eared Owl, Long-eared Owl

- Small owls (150-250mm): Eastern Screech-Owl, Western Screech-Owl, Northern Saw-whet Owl

- Miniature owls (less than 150mm): Elf Owl, Northern Pygmy-Owl, Pearl-spotted Owlet.

Body proportions also aid identification; whether an owl appears stocky, elongated, or compact can distinguish between similar-sized species.

Comparative Analysis of Owls Across Regions

Global Owl Species Comparison Table

| Species | North America | United Kingdom | Canada | Australia | Size (Length) | Distinctive Features | Conservation Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barn Owl (Tyto alba) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 33-39 cm | Heart-shaped white face, golden-buff upperparts | Least Concern (declining in UK) |

| Great Horned Owl (Bubo virginianus) | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | 46-63 cm | Prominent “ear” tufts, yellow eyes | Least Concern |

| Snowy Owl (Bubo scandiacus) | ✓ (winter) | Rare visitor | ✓ | ✗ | 52-71 cm | White plumage, yellow eyes, no ear tufts | Vulnerable |

| Barred Owl (Strix varia) | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | 43-50 cm | Brown barring on chest, no ear tufts, dark eyes | Least Concern |

| Tawny Owl (Strix aluco) | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | 37-43 cm | Rounded head, dark eyes, rusty-brown plumage | Least Concern |

| Northern Saw-whet Owl (Aegolius acadicus) | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | 17-22 cm | Small size, no ear tufts, yellow-green bill | Least Concern |

| Little Owl (Athene noctua) | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | 21-23 cm | Small size, white “eyebrows,” yellow eyes | Least Concern (introduced to UK) |

| Burrowing Owl (Athene cunicularia) | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ (summer) | ✗ | 19-25 cm | Long legs, ground-dwelling, active by day | Least Concern (declining) |

| Long-eared Owl (Asio otus) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | 35-40 cm | Tall ear tufts, orange-yellow eyes | Least Concern |

| Short-eared Owl (Asio flammeus) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | 34-43 cm | Small ear tufts, yellow eyes, diurnal hunting | Near Threatened |

| Eastern Screech-Owl (Megascops asio) | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ (limited) | ✗ | 18-23 cm | Small size, ear tufts, red or grey morphs | Least Concern |

| Western Screech-Owl (Megascops kennicottii) | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | 19-26 cm | Small size, ear tufts, grey-brown plumage | Least Concern |

| Great Grey Owl (Strix nebulosa) | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | 61-84 cm | Very large, grey facial disc with concentric rings | Least Concern |

| Northern Hawk Owl (Surnia ulula) | ✓ | Rare visitor | ✓ | ✗ | 36-43 cm | Long tail, diurnal, hawk-like flight | Least Concern |

| Powerful Owl (Ninox strenua) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | 60-65 cm | Australia’s largest owl, yellow eyes | Vulnerable |

| Southern Boobook (Ninox boobook) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | 27-36 cm | Small compact owl, white spotting, yellow eyes | Least Concern |

| Barking Owl (Ninox connivens) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | 40-45 cm | Dog-like “woof woof” call, yellow eyes | Least Concern |

| Masked Owl (Tyto novaehollandiae) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | 40-50 cm | Heart-shaped face, dark eyes, larger than Barn Owl | Near Threatened |

Regional Owl Distribution Highlights

North America

North America has the highest owl diversity among the compared regions, with 19 regularly breeding species. The continent features unique species like the Elf Owl (world’s smallest owl) and the Northern Pygmy-Owl. The Great Horned Owl serves as the region’s apex nocturnal predator, occupying virtually every habitat from desert to Arctic treeline.

United Kingdom

The UK has a more limited owl fauna with five resident species, but each occupies a distinct ecological niche. The Tawny Owl dominates woodland habitats, while the Barn Owl hunts over open country. The Little Owl, introduced in the 1880s, has become fully established in agricultural landscapes. The Long-eared and Short-eared Owls are less common but regular breeders.

Canada

Canada’s owl community closely resembles that of the northern United States but includes several boreal specialists like the Great Gray Owl, Boreal Owl, and Northern Hawk Owl that are rare or absent farther south. During harsh Arctic winters, Snowy Owls may move southward into southern Canadian provinces in what are known as “irruptive” migrations.

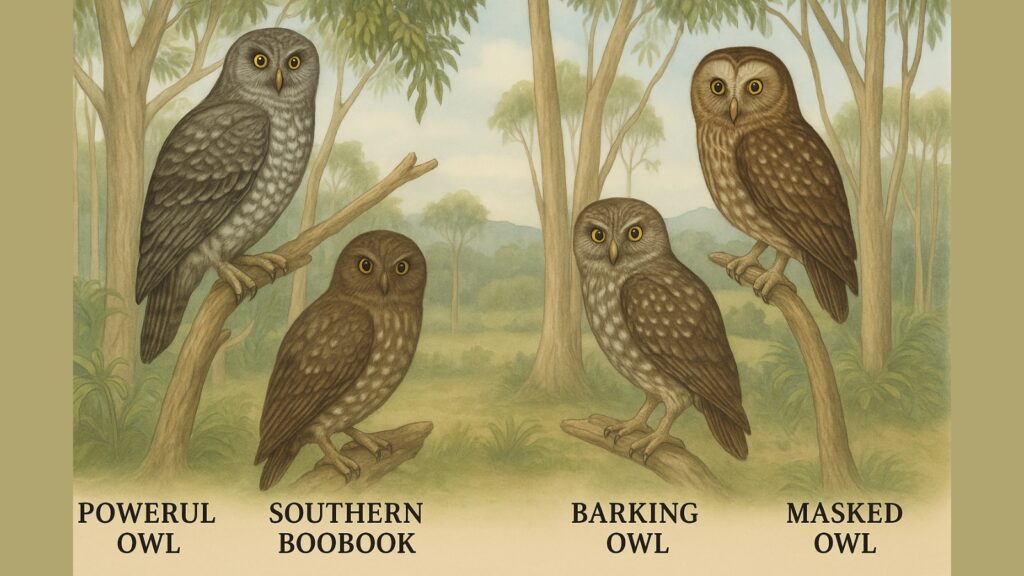

Australia

Australia hosts a completely distinct owl fauna dominated by the Ninox genus (boobooks). The Powerful Owl stands as Australia’s largest owl species and a top predator in eastern forests. Unlike many other regions, none of Australia’s owl species possess prominent ear tufts. The Southern Boobook fills the ecological niche occupied by screech-owls in North America.

Vocalization Comparison

| Region | Common Species | Primary Call Description | Best Time to Hear |

|---|---|---|---|

| North America | Great Horned Owl | Deep “hoo-h’HOO-hoo-hoo” | Dusk to midnight |

| North America | Eastern Screech-Owl | Descending whinny or monotone trill | Early evening |

| United Kingdom | Tawny Owl | Classic “ke-wick” and “hoo-hoo-ooo” | 9pm-midnight |

| United Kingdom | Barn Owl | Eerie screeching or hissing | Throughout night |

| Canada | Boreal Owl | Rapid “po-po-po-po” | Late winter nights |

| Australia | Southern Boobook | Double “mo-poke” call | Throughout night |

| Australia | Powerful Owl | Slow, deep “woo-hoo” | Early evening |

Behaviour-Based Identification Techniques

Vocalization Patterns

Owl calls provide some of the most reliable identification cues, especially at night when visual identification is challenging. Unlike many birds, owls have highly distinctive vocalisations with limited regional “dialects,” making sound a more consistent identifier than appearance.

Common vocalisation types include:

- Hoots: Deep, resonant calls typical of larger owls like the Great Horned Owl’s distinctive “hoo-h’HOO-hoo-hoo”

- Screams/Shrieks: The Barn Owl’s eerie screech or the Eastern Screech-Owl’s descending whinny

- Whistles: The Northern Saw-whet Owl’s monotonous tooting or the Boreal Owl’s staccato notes

- Barks/Yelps: The Burrowing Owl’s chuckling call or the Spotted Owl’s barking series.

Remember that many owl species have extensive vocal repertoires, including alarm calls, juvenile begging calls, and courtship vocalisations, all useful for identification by ear.

Flight Patterns and Hunting Techniques

Owls employ distinctly different flight patterns that can aid identification even in poor light:

- Silent, moth-like flight: Barn Owl, Tawny Owl, Long-eared Owl

- Direct and powerful flight: Great Horned Owl, Snowy Owl

- Buoyant, gliding flight: Short-eared Owl hunting over open fields

- Undulating flight: Northern Pygmy-Owl, resembling a woodpecker’s flight pattern.

Hunting techniques further distinguish species:

- Perch-and-pounce: Most woodland owls, including the Tawny Owl and Northern Hawk Owl

- Quartering low over open ground: Short-eared Owl, Barn Owl

- Hawking insects mid-air: Flammulated Owl, Northern Pygmy-Owl

- Ground-dwelling hunting: Burrowing Owl running down prey on foot.

Activity Periods

While owls are traditionally considered nocturnal, many species have more nuanced activity patterns that help with identification:

- Strictly nocturnal: Barn Owl, Great Horned Owl, Long-eared Owl

- Crepuscular (active at dawn and dusk): Short-eared Owl, Burrowing Owl

- Diurnal (day-active): Northern Hawk Owl, Northern Pygmy-Owl, Snowy Owl (especially in Arctic summer)

- Cathemeral (active in both day and night): Snowy Owl, Northern Hawk Owl.

Activity patterns sometimes shift seasonally or in response to prey availability, making this a contextual identification cue.

Regional Owl Identification

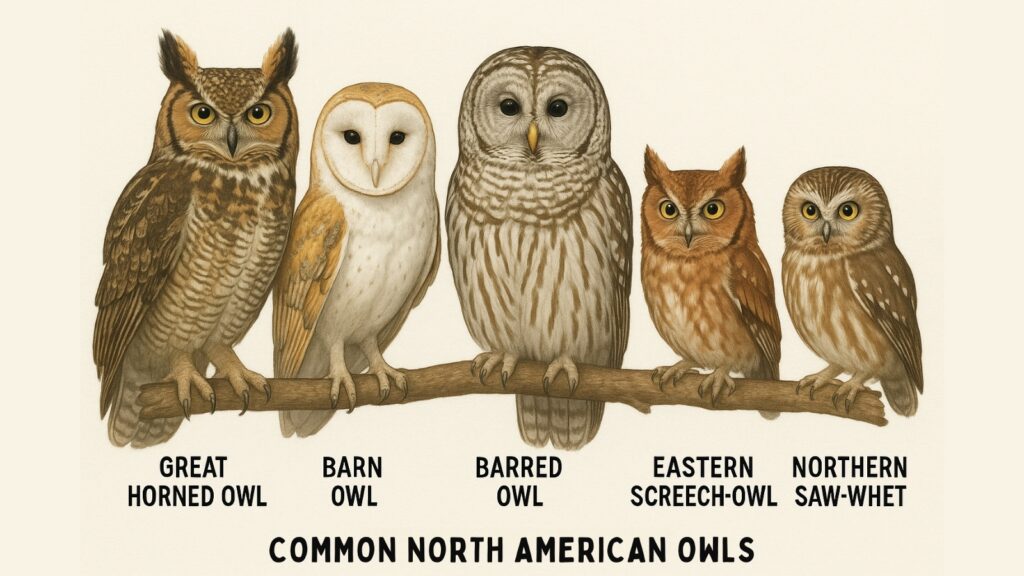

North American Owls

North America hosts 19 regularly breeding owl species plus occasional visitors. Key identification challenges include:

- Screech owl species separation: Eastern vs. Western Screech-Owls are nearly identical visually but have different calls (Eastern: descending whinny; Western: bouncing ball trill)

- Great Horned Owl subspecies: Tremendous variation in colouration from pale desert forms to dark Pacific varieties

- Saw-whet vs. Boreal Owl: Similar small owls distinguished by different facial patterns and vocalisations.

The most widespread North American species include:

- Great Horned Owl (Bubo virginianus): Found in virtually all habitats from desert to Arctic treeline

- Barred Owl (Strix varia): Eastern forests, expanding westward

- Eastern Screech-Owl (Megascops asio): Eastern deciduous forests and suburbs

- Western Screech-Owl (Megascops kennicottii): Western forests and deserts

- Barn Owl (Tyto alba): Open country, farmland, and grasslands.

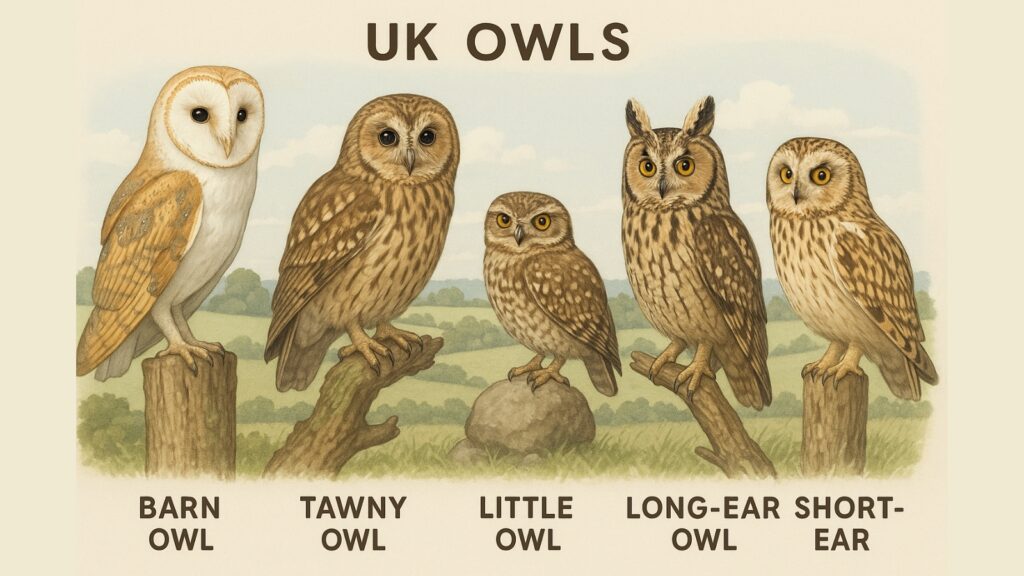

European and UK Owls

Europe hosts fewer owl species than North America but presents its own identification challenges, particularly with the five resident UK species:

- Barn Owl (Tyto alba): White underparts, golden-buff upperparts, heart-shaped face

- Tawny Owl (Strix aluco): The UK’s most common owl, brown or grey with large dark eyes

- Little Owl (Athene noctua): Introduced to Britain in 1880s, small with distinct white “eyebrows”

- Long-eared Owl (Asio otus): Medium-sized with prominent ear tufts, often forms winter communal roosts

- Short-eared Owl (Asio flammeus): Open country hunter, often seen in daylight over marshes and moorlands.

Continental Europe adds several notable species including:

- Eurasian Eagle-Owl (Bubo bubo): Europe’s largest owl, with massive size and prominent ear tufts

- Ural Owl (Strix uralensis): Northern and Eastern European forests

- Tengmalm’s Owl (Aegolius funereus): The European equivalent of the North American Boreal Owl.

Tropical and Neotropical Owls

The tropics host the greatest owl diversity, particularly in the Amazon Basin and Southeast Asian rainforests. Key identification challenges include:

- Dense vegetation limiting visibility

- Higher species diversity in smaller geographic areas

- Many species looking extremely similar (especially screech-owls).

Notable tropical species include:

- Spectacled Owl (Pulsatrix perspicillata): Large tropical owl with distinctive white “spectacles” around eyes

- Crested Owl (Lophostrix cristata): Unique appearance with prominent ear tufts and “eyebrows”

- Tropical Screech-Owl (Megascops choliba): Widespread throughout Central and South America

- Mottled Owl (Strix virgata): Common but secretive forest owl.

In tropical regions, vocalisation identification becomes especially important, as visual observation opportunities are often limited.

Asian Owls

Asia hosts incredible owl diversity, from the massive Blakiston’s Fish Owl (world’s largest owl species) to tiny scops-owls. Regional identification challenges include:

- High species diversity in India and Southeast Asia

- Many endemic island species with restricted ranges

- Several look-alike species pairs requiring careful observation.

Key Asian species include:

- Brown Fish Owl (Ketupa zeylonensis): Widespread across South and Southeast Asia

- Asian Barred Owlet (Glaucidium cuculoides): Common small owl of Southeast Asian forests

- Collared Scops-Owl (Otus lettia): Widespread in urban and forested areas

- Spot-bellied Eagle-Owl (Bubo nipalensis): Large, powerful forest hunter.

African and Middle Eastern Owls

Africa’s diverse habitats support a wide range of owl species adapted to environments from desert to rainforest. Key identification challenges include:

- Desert species often having pale, camouflaged plumage

- Forest species being particularly secretive and difficult to observe

- Many species being poorly documented compared to European or North American counterparts.

Notable African species include:

- Verreaux’s Eagle-Owl (Bubo lacteus): Massive owl with pink eyelids

- Pel’s Fishing Owl (Scotopelia peli): Large rufous owl specialised for catching fish

- African Wood Owl (Strix woodfordii): Common forest owl with distinctive call

- Pearl-spotted Owlet (Glaucidium perlatum): Small, day-active owl with “false eyes” on the back of its head.

Oceania and Australian Owls

Australia, New Zealand, and the Pacific islands host several unique owl species, including:

- Powerful Owl (Ninox strenua): Australia’s largest owl

- Southern Boobook (Ninox boobook): Australia’s most common owl

- Morepork (Ninox novaeseelandiae): New Zealand’s only living native owl

- Barking Owl (Ninox connivens): Named for its dog-like vocalisation.

Island endemics are particularly vulnerable to habitat loss and introduced predators, making conservation status an important consideration when seeking these species.

Advanced Identification Techniques

Seasonal Variations

Many owl species show seasonal changes that can affect identification:

- Moulting patterns: Most owls undergo a complete annual moult, potentially changing appearance slightly

- Juvenile plumage: Young owls often differ from adults, typically having fluffier, looser plumage and sometimes different colouration

- Sexual dimorphism: In many species, females average 5-25% larger than males.

Environmental Factors Affecting Identification

- Lighting conditions: Owls may appear dramatically different in daylight versus moonlight or artificial light

- Weather effects: Wet plumage can darken apparent colouration

- Habitat background: The same species can be more challenging to spot in different environments

Identifying Owls Without Seeing Them

Many owl encounters involve indirect evidence rather than visual sightings:

- Pellet identification: Owl pellets contain undigestible prey remains and vary by species in size, shape, and content

- Feathers: Moulted feathers can be identified by size, pattern, and structure

- Whitewash: Excrement patterns below roost sites

- Prey remains: Different owl species leave characteristic signs on prey.

Conservation Status and Ethical Observation

Global Conservation Challenges

Many owl species face significant threats:

- Habitat loss: Particularly forest fragmentation and old-growth forest destruction

- Urbanisation: Light pollution, traffic mortality, and rodenticide poisoning

- Climate change: Shifting prey availability and habitat suitability

- Direct persecution: Still common in some regions despite protection laws.

Notable conservation status examples:

- Endangered: Blakiston’s Fish Owl, Forest Owlet, Seychelles Scops-Owl

- Vulnerable: Spotted Owl, Long-whiskered Owlet, Madagascar Red Owl

- Near-threatened: Short-eared Owl, Austral Pygmy-Owl, Cloud-forest Pygmy-Owl.

Ethical Observation Practices

When seeking owls, follow these guidelines to minimise disturbance:

- Keep an appropriate distance from roosting or nesting sites

- Limit use of flash photography, particularly at night

- Never use playback calls during breeding season

- Avoid revealing specific locations of sensitive species online

- Keep visits to known owl roosts brief and infrequent.

Practical Field Identification Tips

Best Times for Owl Observation

- Dawn/dusk: Ideal for most species during activity transitions

- Full moon nights: Improved visibility for nocturnal species

- Winter: Reduced foliage improves visibility; some species form communal roosts

- Early spring: Peak vocalisation during courtship and territory establishment.

Essential Equipment for Owl Identification

- Binoculars: 8×42 or 10×42 with good low-light performance

- Spotlight/torch: With red filter to minimise disturbance

- Sound recording equipment: For documenting calls for later identification

- Field guide: Ideally region-specific with vocalisation descriptions

- Thermal or night vision: For serious owl researchers and photographers.

Conclusion

Owl identification represents one of birdwatching’s most rewarding challenges, requiring patience, knowledge, and ethical practices. By combining traditional visual identification with behavioural cues, habitat awareness, and acoustic recognition, you’ll develop a more holistic approach to finding and identifying these enigmatic birds.

Remember that successful owl identification often requires repeated observations under different conditions. Each encounter builds your experience and understanding of these remarkable birds. As owl populations face growing threats worldwide, responsible observation and citizen science contributions have never been more important for conservation efforts.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: What owl species is the most widespread globally?

A: The Barn Owl (Tyto alba) is the most widely distributed owl species, found on every continent except Antarctica. Its range extends across North and South America, Europe, Africa, Asia, and Australia, with various subspecies adapted to local conditions.

Q: How can I tell the difference between male and female owls?

A: In most owl species, females are 5-25% larger than males but otherwise look identical. This size difference is most noticeable when pairs are seen together. A few species show subtle plumage differences, but these are exceptions rather than the rule.

Q: Which owl has the best hearing?

A: The Barn Owl has the most sensitive hearing of any tested animal. Its asymmetrical ear openings—with one ear higher than the other—allow it to triangulate the precise location of prey by sound alone, even in complete darkness.

Q: Do owls really turn their heads 360 degrees?

A: No owl can rotate its head a full 360 degrees, but many species can turn their heads up to 270 degrees (three-quarters of a circle) thanks to specialised blood vessels and extra vertebral connections that prevent blood supply disruption during extreme rotation.

Q: Why do some owls have ear tufts?

A: Ear tufts are not related to hearing but serve multiple purposes: camouflage (breaking up the owl’s silhouette against tree bark), species recognition during mating, and communication of mood or alertness levels. They can be raised when the owl is alarmed or flattened when it’s relaxed or trying to appear inconspicuous.

Q: What’s the smallest owl in the world?

A: The Elf Owl (Micrathene whitneyi) of the southwestern United States and Mexico is generally considered the world’s smallest owl, weighing just 35-55 grams (about the weight of a golf ball) and measuring around 13-15 cm (5-6 inches) in length.

Q: Can owls see during daylight?

A: Yes, all owls can see during daylight, though their vision is optimised for low-light conditions. Many species have pupils that can contract substantially in bright light. Some species, like the Northern Hawk Owl and Burrowing Owl, are regularly active during daylight hours.

Q: How long do owls live?

A: Lifespan varies significantly by species. Smaller owl species typically live 5-10 years in the wild, while larger species may live 10-20+ years. In captivity, these numbers can double. The oldest recorded wild Great Horned Owl was 28 years old, while captive individuals have reached over 50 years.

Q: Do owls migrate?

A: Some owl species migrate while others are resident year-round. The Snowy Owl conducts irregular “irruptive” migrations southward when lemming populations crash in their Arctic breeding grounds. Long-eared and Short-eared Owls often make seasonal movements, while species like the Great Horned Owl and Tawny Owl typically remain in their territories throughout the year.

Q: How can I attract owls to my property?

A: To attract owls, maintain mature trees for roosting and nesting, install appropriate nest boxes, create natural areas with native plants that support prey species, avoid using pesticides and rodenticides, and maintain water sources. Be patient—establishing an owl-friendly habitat takes time.

Other Recommended Owl Resources:

- The Owl Research Institute

“Owl Species Identification Guide” (2023)

https://www.owlresearchinstitute.org/species-id-guide

Provides comprehensive identification information for all 19 owl species that breed in the United States and Canada, developed by leading owl researchers with decades of field experience. - Cornell Lab of Ornithology

“All About Birds: Owl Species Guides” (2024)

https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/browse/shape/Owls

One of the world’s most respected ornithological institutions offering scientifically accurate identification resources with extensive multimedia elements. - The Barn Owl Trust

“UK Owl Species” (2024)

https://www.barnowltrust.org.uk/barn-owl-facts/uk-owl-species/

Definitive guide to the five resident owl species in the United Kingdom, with detailed identification guidance and conservation information. - The Owl Pages

“Owls of the World” (2023)

https://www.owlpages.com/owls/

Long-established comprehensive resource covering all aspects of owl biology, behavior, and identification for species worldwide.